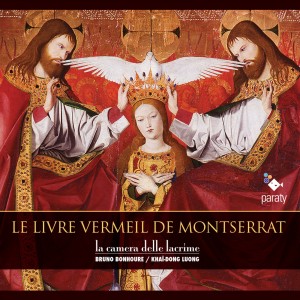

It is thanks to a precious manuscript, the fruit of a compilation completed at the very end of the 14th century and preserved in the Abbey of Montserrat’s library, that we know of the monks’ design. Only 137 of the original 172 folios have survived. Among the numerous liturgical or administrative documents, there is a short songbook (f.21v-27) comprising ten anonymous songs. A note placed between the first two songs specifies its mission: to assist those pilgrims who wish to occupy themselves with singing and dancing during their vigil in the church of the Blessed Mary of Montserrat, as much as outdoors during the daytime (“Quia interdum peregrini quando vigilant in ecclesia Beate Marie de Monte Serrato volunt cantare et trepudiare, et etiam in platea de die”), on condition that the songs remain decent and pious (“nisi honestas ac devotas cantilenas cantare”) and that care is taken not to disturb those who are deep in prayer or in devout contemplation (“ne perturbent perseverantes in orationibus et devotis contemplationibus”). Not that simple…

Fashioned for the meeting place that was Montserrat, uniformity is scarcely the rule here, no more in the music itself (four monodies versus six 2-, 3- or 4-voice polyphonies) that in its notation (the style introduced by Philippe de Vitry around 1315-1320 rubs shoulders with the square notes of Gregorian parchments), nor in language, with liturgical Latin (eight songs) competing with the local Catalonian, so closely related to Occitan (two); nor in the choreographic options, with four songs being accompanied by rounds (ball a redon in Catalan), circle dances where the dancers join hands. The whole assumes its own heterogeneity, from its most ancient borrowings to its most modern biases, even when the latter are wrapped in a “quaint” old style. A heterogeneity akin to that of the pilgrims themselves, men and women from every land and every background jumbled together in fraternal unity – the same unity that gathers them, no longer smiling, in those Dances of Death that were spreading over church walls as these songs were compiled, deriding human vanity.

Across the centuries, the songs and dances that echoed in the Abbey-Church of Montserrat retain all the flavour of their uniqueness.

We cannot gauge the gap between these outbursts of popular music and the plainsong tradition fostered by the monks of Montserrat, as fires greatly depleted the treasures held in the library of this holy place, to say nothing of the sacking of the monastery by Napoleonic troops during the 1811 campaign. Luckily, the 1399 manuscript was not currently there, having been loaned out for study to an erudite Barcelonian. Who piously kept it. When, half a century later, his descendants restored it to Montserrat, the monks clothed it in a cover of wood and red velvet, earning it its contemporary name of Llibre Vermell de Montserrat. By the latter part of the 19th century, the compendium had acquired so great a renown that it was catalogued as the very first volume of the new monastic library that its return symbolically re-established.

And it is under this name, which might have been plucked from one of Chrétien de Troyes’s romances, that this incredible document is now known. A worthy salute to the legendary imaginings it illustrâtes.

La Camera delle Lacrime

La Camera delle Lacrime