Who can forget Pierre-François Lacenaire, brought to life on screen in Jacques Prévert and Marcel Carné’s legendary film Children of Paradise [Les Enfants du Paradis] by Marcel Herrand, rubbing shoulders with Arletty, Pierre Brasseur and Jean-Louis Barrault?

The Antihero of French cinema’s most beautiful film, Pierre-François Lacenaire was above all a true human enigma, a moral and social “monster” in the eyes of his contemporaries. Condemned to death in November 1835 for having committed more than 16 crimes, he was incarcerated in the Conciergerie [a Parisian prison] for several months preceding his execution in January 1836. This is when he became a cultural phenomenon, an attraction for those who wished to get close to him, rub shoulders with him, and interrogate him. The reason is because Lacenaire, throughout his imprisonment, wrote memoirs, poetry and songs. His imminent date with the guillotine became a source of inspiration: “La lucarne” (as the guillotine was nicknamed, from the resemblance of the circle that pins the neck to a small window) became his muse.

His work went on to fascinate many a writer and intellectual, including Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes; but doubtless it was Flaubert who gave him his greatest encomium: “Lacenaire was also a philosopher, in his manner […] he gave such a lesson to morality, he really spanked it publicly…”

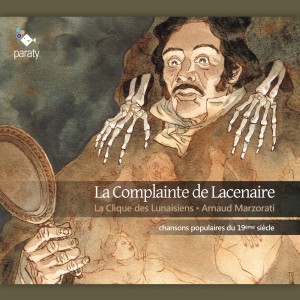

The monstrous Lacenaire’s songs and poems are the “flowers of evil” of our new recording. The more we rediscovered his repertoire, the more we realised what an incredible writer Lacenaire was, possessed of powerful verve, and inventive in his daydreams. Like Byron he plunges us into a fantastic and romantic universe. The condemned poet-assassin’s “Sylphide” and “Dreams” defy death and the guillotine as he recites his last song, like Lamartine’s swan. His contemporaries spoke of him “wielding both lyre and dagger,” and said that he sang like the poet André Chénier and murdered like the criminal “Cartouche”.

Lacenaire’s Lament is the last will and testament of a child of the “boulevard du crime”, just as the Ballad of the Hanged was that of François Villon, another poet-assassin. This criminal knew how to sing; he knew his classics, like The Drunkard and the Penitent or Jesus Christ Dresses like the Poor, to be found in the vocal repertoire of the Romancero Français rediscovered by the poet Gérard de Nerval; but he also knew the works of the 19th century’s greatest popular singer in France, Pierre-Jean de Béranger, whom he tried to convert to his literary cause.

Was he a misunderstood artist, condemned by society? Or a degenerate, perverse bogeyman, too dangerous for his fellow creatures? We wouldn’t dare summon this fallen poet to judgment, but neither would we dare whitewash the portrait of a self-confessed criminal. But we did take incomparable pleasure in singing this individual’s adventure and his ambiguous relationship with conventional morality.

To accompany us on this undertaking, we asked the illustrator Maël to depict the universe of this half-brother of Maldoror. We wanted his drawings to have a place in Lacenaire’s Legend. Between Goya and Daumier, Maël’s drawing-pen offers a striking, dramatic line that once more sketches Lacenaire, leaving caricature aside with a precision that reinforces the enigma of our poet-assassin.